When Florence was the cultural and financial capital of the Renaissance, it contained scarcely 70,000 inhabitants. On foot, one could traverse this glorious city in twenty minutes from one side to the other. In the fifteenth century the most populous cities of Europe -- Paris, Milan and Venice -- contained no more than 100,000 people and already Leonardo da Vinci was proposing to divide his city into five autonomous riones (quarters).

Before 1800, and with the exception of Cologne, each of the most powerful and prestigious of the 150 German cities had no more than 35,000 inhabitants; Nuremberg had about 20,000. If the German architect, urbanist and teacher Heinrich Tessenow affirmed that there was a strict relationship between the economic and cultural wealth of a city on the one hand, and the limitation of its population on the other, he was advancing not a hypothesis but a historical fact. By cultural and material wealth he did not mean absolute power, but the just and harmonious relationship established between the citizens of a city and its territory.

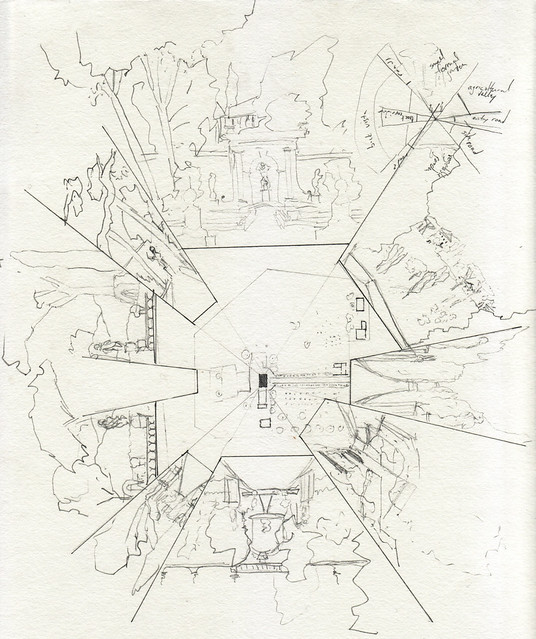

In contrast to the zones of an industrialized territory, the measurements and geometric organization of a city and of its quarters are never the result of chance or accident or simply of economic necessity. The measurements and geometric order of a city and of its quarters constitute a project which is moral and legislative, technical and aesthetic.

As the glove and the shoe are the accomplished forms used to cover hands and feet, similarly the house and the street, the palace and the square are the just types and forms to shelter and protect the social life of a people.

It is a fact that a city of more than 50,000 inhabitants will not succeed in living solely on the resources of its surrounding territory unless blessed by the most clement of climates. Beyond a certain size, the mere logistics of supply and distribution become the principal aim of civic life; thus the majority of citizens are employed in the branches of distribution, administration, and services. Instead, we should realize that the right form of the city exists only in the right scale. An object that imitates a glove but which weighs ten tons is not a glove.

In violent opposition to the designers of industrial projects, in contrast to the numerous teachings of the Bauhaus, the Deutscher Werkbund, or the Nazi Deutsche Arbeits Front (DAF), there is no reason to believe that the measurements of the city and of its parts lie in mathematical precision. We are not interested in utopias or ideal projects and we refuse to occupy ourselves with ideal and abstract measurements. Such preoccupations are characteristic of merchants and policemen; they always confuse the notions of type and standard, of normality and norm. Monsters and midgets define the limits of normality; one by excess, the other by insufficiency. In order to define a normal measure it is thus sufficient for us to indicate limits, that is to say, the maximum and the minimum.

But measure does not only concern the geometric dimension of spaces and objects of the city and its quarters, but also the size of human communities. Like a tree or a man, a human community cannot exceed a certain dimension without becoming a monster; either a giant or a dwarf. As Aristotle said: "To the size of cities there is a limit as is the case with everything, with plants, animals, tools; because none of these can retain its natural power if it is too large or too small, for it then loses its nature or it is spoilt" (Aristotle, Politics).

Similarly, Galileo maintained that a man of 100 meters in height made of flesh and bone would imprison himself and would be incapable of living on this planet. The Pythagoreans taught that evil belonged to the realm of the limitless and that good belonged to that which was limited. Aristotle made this truth the foundation of everything: philosophy, ethics, and by consequence, of politics and culture.

Just as proper measure is the condition of all life, so the vitality of a community overdevelops or atrophies according to the number of its inhabitants; a city can die by an abnormal expansion, density or dispersion. And just as a family does not grow through the swelling of the parents' bodies but through the birth of children, so an urban civilization cannot with impunity grow beyond the exaggerated swelling of human agglomerations. "A tree grows freely --", wrote the progressive German industrialist and anti-Nazi statesman Walther Rathenau, "-- that doesn't mean that it is going to decamp or for that matter grow up to the sky".

The free and harmonious growth of an urban civilization cannot be accomplished except by the right and judicious geographical distribution of its cities and communities, which have to be autonomous and finite. Only then will cities know how to respond to the economic functions of a community and satisfy the highest aspirations of the spirit.

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu